The Project

Notizbuch von Theodor Schwann

Image: Privatarchiv Hannes BöhringerProject Manager: Dr. Florence Vienne

Hardly any 19th century natural scientist is so well-known and also so unknown as Theodor Schwann (1810-1882). Textbooks and history books remind us of his discovery of cells as the basic unit in plants and animals. Alongside Darwin’s theory of evolution, cell theory is one of the foundations of the biological sciences. However, while the many and diverse facets of Darwin the natural scientist have long since been researched on the basis of his Nachlass manuscripts, Schwann’s life and work remains mostly unexplored. His extensive unpublished work has hitherto remained largely unknown. This includes experimental and scientific records, personal diaries as well as drafts and the manuscripts of his lectures. He kept a diary as a young assistant to the physiologist Johannes Müller (1801-1858) in Berlin in the 1830s and as a university lecturer in Leuven and Liège from 1839 up to the 1870s. His records document his work on the genesis of his 1838 cell theory but also its later further developments. They provide insights into the metaphysical and theological questions that shaped his worldview and scientific outlook from his youth up to his death. Like the botanist Jakob Matthias Schleiden (1804-1881) and the zoologist Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919), Schwann left behind a body of work that is an expression of a profound scientific and cultural transformation. Using the example of the three biologists, we can explore the reciprocal relations between the emergence of a cellular understanding of the living organism and the religious and political upheavals of the 19th century.

The Project

This project was financed by the DFG and it was based at the Technische Universität Braunschweig from 2017 to 2020. It has continued from December 2020 at the Ernst-Haeckel-Haus of the Friedrich Schiller University Jena under the directorship of Dr. Florence Vienne.

In the autumn of 2021, a key component of Schwann’s Nachlass, previously held by the Museum for the History of Medicine in Berlin, was given on loan to the Friedrich Schiller University.

This project aims to make Schwann’s unpublished work better known and more accessible to the research community. An index of the manuscripts he left behind will soon be published and made accessible in digital format. Furthermore, digitalized writings will made available online via the access platform for multimedia offerings of the University and State Library Jena. Finally, key sources will be transcribed and edited. Opening up Schwann’s unpublished writings will not only enable an overall view of his life, research and thinking. Parallel to the research on Matthias J. Schleiden (1804-1881) and Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919), the project will also open up new perspectives in the history of science regarding the interrelations between biology, religion and politics in the 19th century.

Transcription and edition of key manuscripts

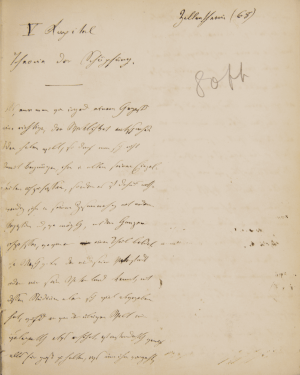

Theodor Schwann, „V Kapitel Theorie der Schöpfung“, undatiert, S.1

Image: Privatarchiv Hannes BöhringerOnly a few of Schwann’s manuscripts are available in transcribed and published form. Up to now, letters (from and to Schwann), excerpts from his personal diaries and one of his numerous experimental notebooks (from 1834-1837) have been published. Undated drafts for a second volume of his 1839 work Mikroskopische Beobachtungen über die Uebereinstimmung in der Struktur und dem Wachsthum der Thiere und Pflanzen[Microscope Observations on the Concordance in the Structure and Growth of Animals and Plants] have remained almost completely unnoticed. They reveal the incomplete character and the theological dimension of his cell theory. A further writing shows that Schwann updated his ‘cellular-theological’ theory in the 1860s and 1870s. An edition of this source material, transcribed by Dr. Jakob Mittelsdorf, is currently being prepared for publication. This first publication from Schwann’s unpublished writings offers a new understanding of the genesis and significance of Schwann’s cell theory.

Theo-political dimensions of cellular biology from Schwann to Haeckel

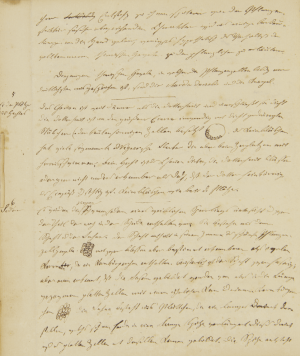

Theodor Schwann, „Ideen naturwissenschaftlichen Inhalts“, Band 1 (1838-1866)

Image: Privatarchiv Hannes BöhringerNineteenth century cell and evolutionary theories are regarded as making important contributions to the emergence of a modern and secular worldview. While the history of science has studied the influence of the philosophy of nature and natural theology on Charles Darwin and Ernst Haeckel for a long time, the role of religion in the history of cell theory has remained largely overlooked. The German founders of cell theory - Matthias J. Schleiden und Theodor Schwann – tend to be regarded in a one-sided fashion as the pioneers of a biology that made a decisive break with then dominant vitalist and metaphysical assumptions. This narrative of progress led to a selective view of their works. In Schwann’s case, most of his unpublished work has gone unnoticed or has been interpreted as the expression of a mysticism that Schwann supposedly fell prey to afterformulating his cell theory. As against this, this project is based on the hypothesis that no clear line of demarcation can be drawn between science and religion in the life and work of the founder of cell theory, from his youth up to his death.

This postulate has a series of implications for the history of science. While classical historiography assumes that the formulation of cell theory presupposed an emancipation from metaphysics, we here inquire into the epistemological significance of metaphysical and theological concepts in the development of 19th century cell theory. Further, Schwann’s cell theory, published in 1838, and its largely unknown further development from the 1840s to the 1870s, is regarded as the expression of profound scientific and cultural transformations.

More particularly, Schwann’s “cellular theology” is read as a response to secularization efforts and revolutionary upheavals in the 19th century that was not unique. For the botanist Schleiden and the zoologist Haeckel too, cell theory was an important point of departure for new examinations of the relationship between body/ matter and mind, religion and the natural sciences, biology and politics. Using the example of the three biologists, the project investigates differences and parallels between their respective counter-concepts to materialistic worldviews. It pays particular attention to the emergence of new forms of politicizing cell biology as well as to new ways in which the human and society were naturalized in the post-revolutionary era of 1848. While Schwann, who was Catholic, continued his work in a French speaking environment from 1839 onwards, Jena was the main field of activity for the Protestants Schleiden and Haeckel. Not least, this approach enables investigating the intertwinements between biology, religion and politics in the 19th century from a transnational perspective.